Folk Art Piece of the Week - Scholar's Choice

Posted on May 21, 2020

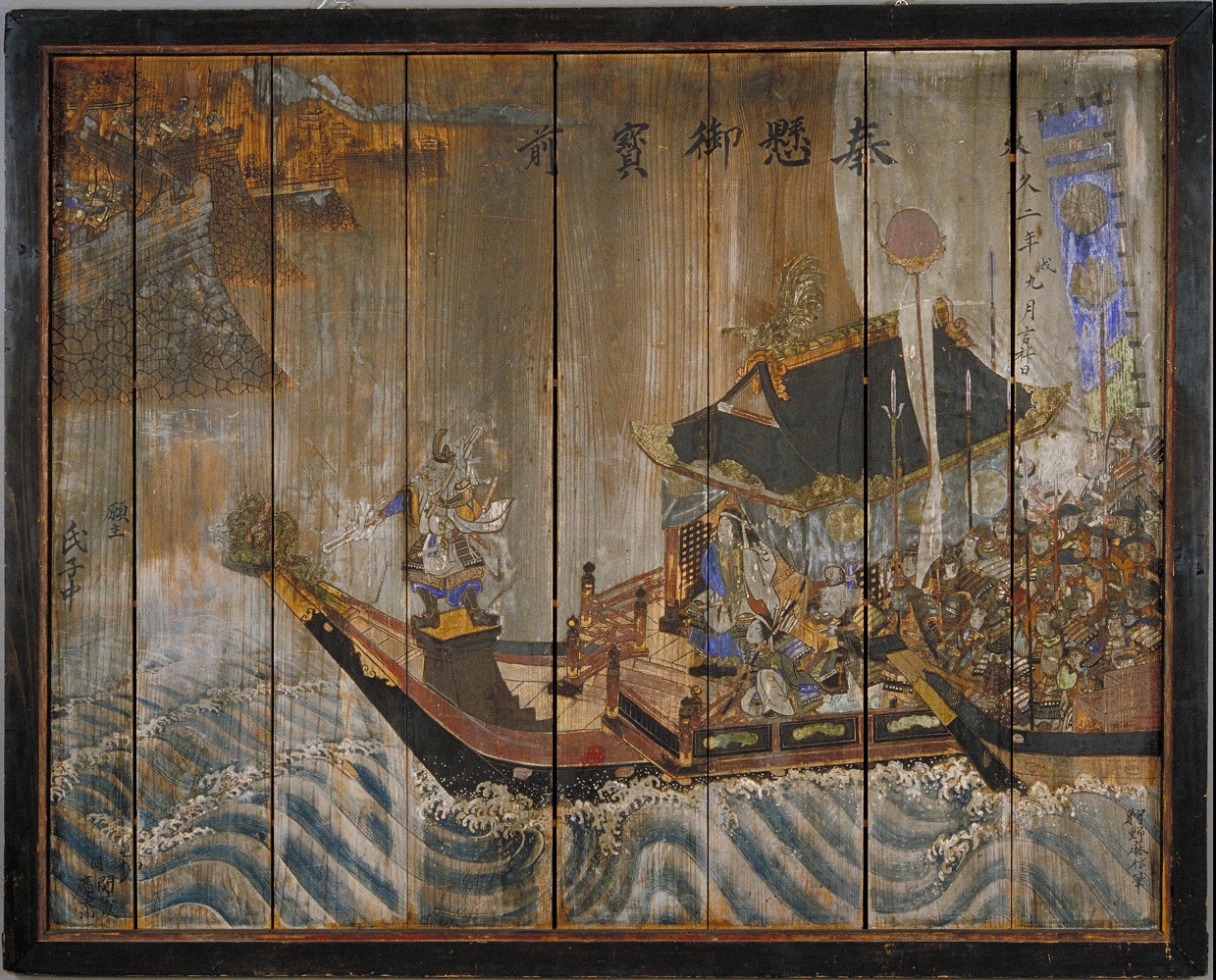

Empress Jingū: Warrior Queen of Myth

A Votive Tablet in the collection of the Museum of International Folk Art

Elizabeth Lillehoj, PhD

Empress Jingū

Shinto votive tablet (ema)

Painted by Kano Asanobu, 1862

Wood, paint

52 inches x 66 inches (132.1 cm x 167.6 cm)

Japan

Museum of International Folk Art, Gift of Lloyd E. Cotsen and the Neutrogena Corporation (A.1995.93.1525)

A famous Japanese myth, the legend of Empress Jingū, is illustrated in this colorful painting on a wooden votive tablet, called an ema. Large ema like this are displayed at Shinto shrines, where visitors view them in an open-air structure or under the eaves of a shrine building. Over the years, the Votive Tablet became weathered and darkened due to outdoor exposure to humidity and sunlight.

Empress Jingū sits in a boat near the center of the Votive Tablet. She gazes out at the Korean shore at far left. Having just arrived with a cohort of gods and soldiers from her homeland on the Japanese archipelago, Jingū is preparing to conquer the Three Kingdoms, which controlled most of the Korean peninsula in the first centuries C.E. According to myth, that is when Empress Jingū was living. However, scholarly consensus holds that Jingū never existed or at most she was semi-historical.

Empress Jingū sits in a boat near the center of the Votive Tablet. She gazes out at the Korean shore at far left. Having just arrived with a cohort of gods and soldiers from her homeland on the Japanese archipelago, Jingū is preparing to conquer the Three Kingdoms, which controlled most of the Korean peninsula in the first centuries C.E. According to myth, that is when Empress Jingū was living. However, scholarly consensus holds that Jingū never existed or at most she was semi-historical.

Jingū’s appearance in the Votive Tablet conveys the grandeur expected of a warrior queen. Not only does she wear armor, she has a sheathed sword, a war fan, and a headband to keep her hair in place during battle. Although pigment has flaked away, we can make out in the under-painting the concentration on Jingū’s face.

Mythic histories identify Jingū as a sorceress who channels voices of the gods and as the wife of Emperor Chūai (149–200). According to two early accounts, Jingū fulfills a divine mission given to Chūai before his death. The mission is to lead forces across the sea and assume control of the Three Kingdoms. Jingū manages this without bloodshed, and upon returning home, she gives birth to a son later known as Emperor Ōjin. The veracity of these accounts is highly suspect, as they were composed under imperial auspices to justify Yamato rule long after Jingū’s purported lifetime.

It is difficult to either prove or disprove claims about Jingū’s existence due to the paucity of records on early Japan, a non-literate culture. Yet, the oldest known written source on prehistoric Japan, a Chinese account of circa 297 entitled “Treatise on the People of Wa,” mentions a female ruler named Himiko who ended a civil war in the second century and ruled Yamatai on the archipelago. It is possible that a distorted memory of Himiko spawned the Jingū legend.

Peoples in East Asia had long been interacting, even before either Korea or Japan came into existence as a single, unified government. A number of premodern kingdoms on the peninsula and the archipelago struggled amongst one another, locally and across the sea. Much more common than armed conflict, however, were extended periods of peaceful exchange.

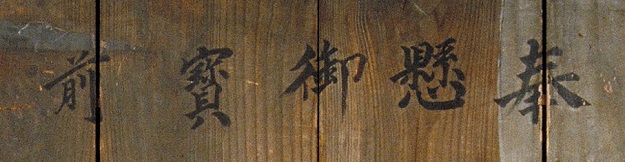

The Votive Tablet has several inscriptions. One is an artist’s signature reading “painted by Kano Asanobu.” Another is a dedication written across the top: “hung and respectfully dedicated to the gods.” A date of 1862 is also inscribed on the tablet.

Shrine visitors who viewed the Votive Tablet in 1862 likely appreciated its martial, monarchial, and sacred features. However, contemporary viewers must have understood that the artist of the Votive Tablet was not portraying actual events. Instead, he was dealing with constructed memories, as well as a mid nineteenth-century perception of Japan’s vulnerability. The artist cloaked this perception in myth to create a hybrid fantasy. What he mainly addressed was a growing anxiety about Western colonial powers encroaching upon Japan and threatening its sovereignty.

Elizabeth Lillehoj is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at DePaul University, Chicago. Her book, Art and Palace Politics in Japan, 1580s–1680s, was published by Brill in the Japanese Visual Culture Series in 2011. She served as editor of several collected volumes, including Archaism and Antiquarianism in Korean and Japanese Art (Art Media Resources and Center for the Arts of East Asia, University of Chicago, 2013), as well as co-editor of Art and Sovereignty in Global Politics (New York: Palgrave, 2017). Before retiring in 2018, she taught various classes on Asian art at DePaul, curated several exhibits of Asian Art, and served as Research Associate of Asian Art, first at the Illinois State Museum and later at the Field Museum of Natural History.

Latest Posts

-

COVID-19 Embroideries

- Nov 10, 2022 -

Guru Mahatmya

- Jul 20, 2021 -

The COVID-19 Pandemic from an Indigenous Perspective

- Feb 17, 2021 -

Docent's Choice

- Jul 23, 2020 -

Folk Art Piece of the Week - Docent's Choice

- Jul 02, 2020